Pull request intervention for infrastructure-as-code risks with Bitbucket custom merge checks

Establishing progressive deployments to control blast radius for the most active types of changes in an architecture is often well worth the investment. But what about those less frequent, or sometimes obscure changes? Learn how Atlassian used the rich integration ecosystem available in Bitbucket and Forge to surface identified risks in our infrastructure-as-code.

Change-related incidents are always one of the largest risks to the reliability posture of a cloud-native organisation like Atlassian. Our incident data indicates that up to 50-60% of service disruptions or degradation can be related to recent changes performed as part of development or maintenance.

But change is fundamentally necessary to providing great products – addressing feedback and requests for features regularly is what enables an ever-improving experience for our customers.

Atlassian’s cloud ecosystem undergoes hundreds of changes every day. To minimise the impact of change-related incidents, Atlassian leverages progressive deployment to gradually expose users to new versions of running code or configuration, limiting the blast radius of a failed change.

To achieve this Atlassian cloud products are hosted in a number of isolated regions, where changes are deployed, monitored, and validated before being promoted to subsequent regions. Within each region a new, immutable stack of infrastructure is deployed with the new code artifact and traffic progressively introduced to this stack. Anomaly detection monitors key metrics like error rates to halt and automate the rollback of a faulty deployment, minimizing the time users are affected.

Continuous integration practices wrap around this deployment process, ensuring that changes to code and configuration that are checked in are clearly documented, peer reviewed, and validated in pre-production tests.

Infrastructure-as-code

Our progressive deployments work as intended, greatly reducing the severity of change-related issues by limiting the number of impacted users as thousands of developers ship changes to Atlassian products each day.

But modern “infrastructure-as-code” tools and practices continue to expand the types of configuration that we manage via version control and deploy via CI/CD pipelines. What we consider “code and configuration” is diverse, with not all types of changes being created equal in how they are deployed.

A key example of Atlassian infrastructure-as-code is the service descriptor: a YAML descriptor file that documents the required configuration for a running Atlassian service – container images, environment variables, service mesh dependencies, database and queue resources, gateway endpoints – you name it, it lives in the service descriptor. Atlassian’s cloud ecosystem is made up of hundreds of independent services, with each service having its own service descriptor.

Just like the running application code for our products, this service descriptor undergoes regular changes to meet evolving requirements – such as new database versions, more resources, or new service dependencies. And just like our application code, these changes are applied automatically by Atlassian platform services as part of the deployment pipeline.

Known Risks in infrastructure changes

Whereas a change to application code to update an API fits neatly into the model for progressive deployment via a canary, something like a PostgreSQL database version upgrade is less trivial to canary to users, let alone rollback.

How often is it a change to a dusty old DNS record that triggers the all-night incident? When something like this breaks, there are grim nods in the post-incident review – everyone saw it coming. It is a known risk.

One of the benefits of engineering at Atlassian’s scale is the ability to find patterns in rare or irregular events like incidents. Over time the data from our post-incident review process exposed a pattern of severe incidents with change-related triggers that shared some important characteristics:

- Large blast radius: These changes demonstrated impact to running services in more than one of our (otherwise) independent running regions, through fundamental configuration or infrastructure that did not participate in progressive deployment. These led to increased impact when something went wrong through a larger cohort of impacted customers.

- Complicated rollback: These changes affected infrastructure or configuration that was unable to be promptly reverted by our automated rollback processes and requiring manual intervention. These led to increased impact when something went wrong through increased Time to Repair (TTR).

Equipped with these two categories, we were able to perform an audit of our broad architecture and configuration management systems to compile a catalogue of Known Risks: identified change types that, when deployed, were known to increase severity of a resulting incident by way of not fitting neatly into the framework of our progressive deployments.

The long tail of risk mitigation

Why did these Known Risks exist in our infrastructure if they have a clear impact on reliability? The answer is risk.

Risk is commonly defined as the product of likelihood, which describes the probability or change that an event could occur, and impact, which describes how severe or damaging it would be if that event were to occur.

Risk explains why most of us are more concerned about trying to ride a skateboard than catching a flight, even though the impact of a accident in our flight is so much more severe than falling off a skateboard. The likelihood is so markedly different as to offset the stark difference in potential impact.

Atlassian products are updated many times every day, with the overwhelming majority of those changes being application code. If shipping application code had the potential impact on every deployment to disrupt all users, that’s a regular catastrophe. The return-on-investment (ROI) on building robust progressive deployment that caters to these changes is clear. As the frequency of a type of change increases, or the cost of implementing progressive deployment increases, the value proposition becomes less clear.

It was not by oversight or unfortunate luck that these Known Risks had manifested in the architecture of our systems and platform. Lack of support for progressive deployment of these changes was adequately explained by a confluence of one or more factors:

- A fundamental limitation of some underlying infrastructure – such as changes to a multi-region database like DynamoDB Global Tables, or an inability to easily rollback a PostgreSQL database version upgrade

- Efforts to incorporate progressive deployments were complex and expensive – such as retrofitting a legacy DNS alias system to conform to our modern view of regions and environment boundaries

- Changes of this type were infrequent – such as configuring service mesh cross-region routing configuration that rarely changed post-bootstrap

Every engineering group dreams of fixing every bug, closing every risk, and shipping every feature. But engineering is a series of tradeoffs – it was only feasible to address and eliminate the root cause of many of our Known Risks on a strategic time scale of multiple quarters.

Catching Known Risks

With a roadmap in place to address our Known Risks architecturally and eliminate the impact, we focused on addressing likelihood in the interim – as a central reliability team how could we ensure these types of changes had the necessary oversight to ensure the heightened risk was managed appropriately?

Atlassian is a “you build it, you run it” engineering organisation with services owners maintaining their code and configuration across hundreds of independent repositories and thousands of changes being deployed every day. It was not feasible to provide manual or otherwise human-driven oversight. The platform documentation was already expansive and detailed, with many of our Known Risks already documented in one place or another.

What we needed was a way to intervene and intercept relevant changes in order to inject the necessary information exactly when it was relevant.

“Woah! Hold up there, did you know that this change won’t rollback if there is an issue with it?”

“Wow, thanks Reliability Team! I never knew. You really saved my bacon!”

Intervening on Bitbucket pull requests

A number of our Known Risks manifested as changes to service descriptors. Pull requests implicated in post-incident reviews were a frequent smoking gun – gosh, poor kid, if only they could have known.

We decided that intervening at the time of the pull request could be an effective way to address these changes. Blocking certain changes within the deployment engine was another option, but was too late in the development lifecycle. It was important that we were able to provide feedback prior to the change being approved and merged to promote an effective developer experience – an integration in our deployment systems would come too late and cause frustration through rework.

JIRA-12345 Take down production and don the cone of shame [low-risk]

– an example implicated pull request title, probably

Bitbucket custom merge checks

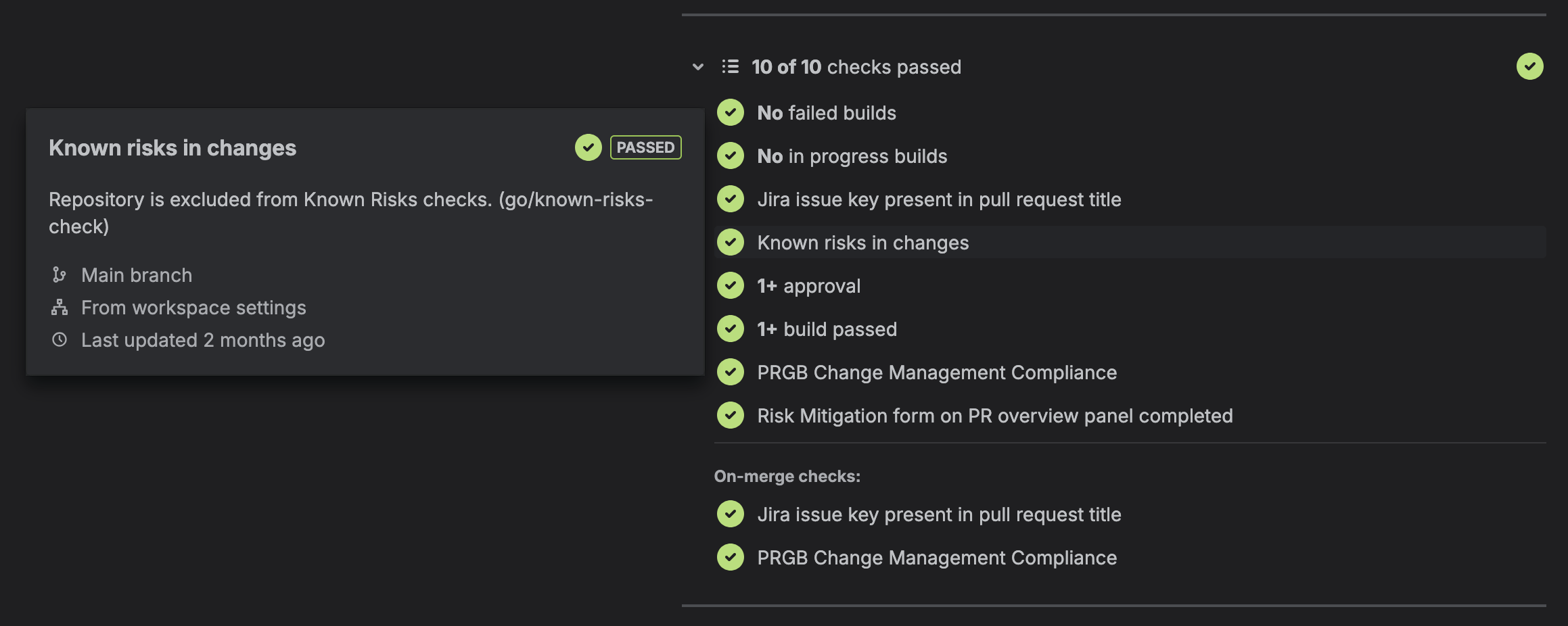

Bitbucket custom merge checks provide us a native hook to invoke just-in-time analysis when a pull request is created or updated. Our analysis and checks are maintained as a standard TypeScript project, deployed using the Forge ecosystem, and managed similar to any other runtime service at Atlassian.

We are able to extend Bitbucket UI experience using a small React application maintained in our service, to provide rich feedback to users and to provide a form to collect approvals.

Our checks are configured and enabled Atlassian-wide through workspace administrators, avoiding the need for attention or action from hundreds of individual service owners.

Learn more about using Forge to power Bitbucket custom merge checks here:

Build a pull request title validator with custom merge checks

Detecting Known Risks

The framework of our Known Risks merge check has four phases:

- Inspect the pull request for files of interest: Native integration with the Bitbucket Cloud REST API within Forge allows the check to enumerate the changed files in a pull request, matching them against a known set of patterns for files of interest. For example, a simplified set of patterns for matching our service descriptor file of interest is

[*.sd.yaml, service-descriptor.yaml] - Evaluate changes to any files of interest: In the case that a file of interest is detected, the current and updates versions of the file are retrieved and passed to an evaluator for that file that understands how to detect Known Risks in that file. For example, our service descriptor evaluator calculates a JSON diff of the two files and performs checks for Known Risks involving DynamoDB, RDS, and others.

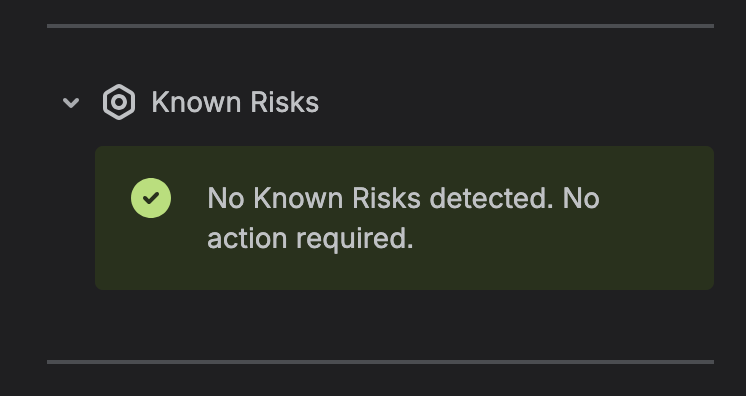

- Report the result: If Known Risks are detected, a clear message is constructed for the user, reporting the detected issues, directing them to guidance on how to proceed, and failing the merge check. If not, the merge check passes.

- User submission approval: The developer raises an approval that documents the monitoring and rollback criteria for the change, has it peer reviewed, and then submits that approval via a Known Risks UI on the PR.

Known Risks in action

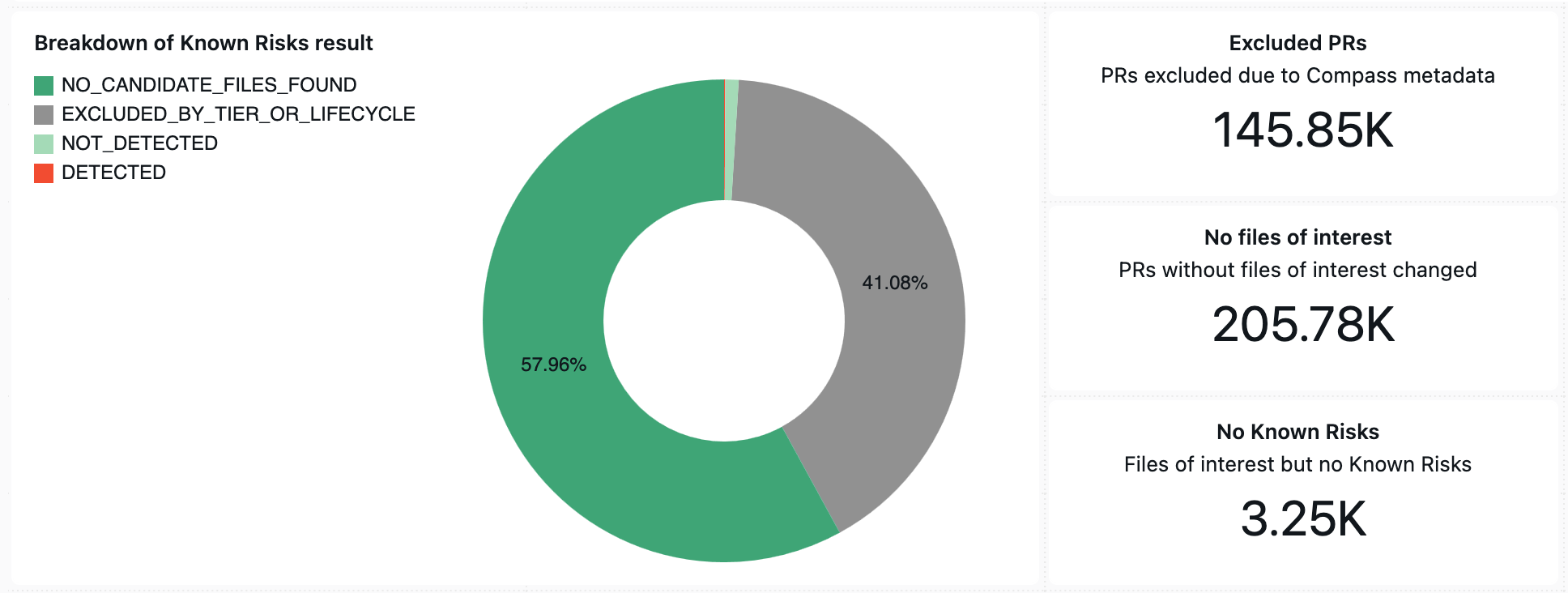

Taking an average 90-day window, we see 5,000-6,000 PRs inspected by Known Risks each weekday, for a total of over 355,000 PRs. These PRs are across over 5,000 unique repositories.

For this window, Known Risks were detected in 258 pull requests, for an overall detection rate of only 0.075% or 7 per 10,000 pull requests.

Looking at our breakdown, about 145,000 pull requests (41%) were excluded because they did not match our criteria (more on this later).

Only 3,250 of the remaining 205,000 pull requests, or 1.6%, contained changes to our files of interest, and then of that small percentage we get the further minority of only 258 Known Risks detected – roughly 8% of changes to files of interest. (files of interest include configuration like service descriptors where possible Known Risks changes have been identified)

What this shows us is that a simpler or more naive approach here, such as a blanket change control process on service descriptor changes, would have been greatly wasteful of developer time and introduced huge amounts of friction. We can see also at play the staggering disproportion between files of interest and more common changes like code updates – almost 100 to 1!

Has Known Risks reduced incidents at Atlassian?

As yet, no pull request flagged by Known Risks has been involved in a severe incident – but there are still change-related incidents at Atlassian so perhaps we’re just not catching the right things yet.

Incidents, and especially change-related incidents, are highly stochastic and variable. Attributing reliability improvements based on rate of incidents is tricky work.

What we are confident in is that our Known Risks checks provide actionable, relevant context and guidance to Atlassian developers and equip them to make great decisions about deploying change.

Reliability and developer experience

One of the key challenges to being a software engineer is the friction introduced into our developer loop by well-intended tools and checks such as Known Risks.

Being embedded in the pull request lifecycle it was a key consideration of our team that Known Risks did not inadvertently interfere with developer life at Atlassian or introduce unnecessary overheads. This is directly linked to achieving our reliability outcomes – process fatigue from systems such as Known Risks encourages people to circumvent or workaround checks and balances where discipline, care, and diligence are key.

This section describes the series of safeguards and enhancements in Known Risks to ensure that our checks avoid unnecessary burden on the developer.

Failing open

Checking for Known Risks is important, but not as important as our ability to ship code at Atlassian. The Known Risks check fails open to an unblocking state if errors occur during checking, in order to avoid blocking developers during outages or issues with Known Risks.

Given the wide diversity of changes that Known Risks attempts to check, there are a baseline of cases that fail parsing – unexpected matches to our files of interest patterns that aren’t of the expected type, template versions of files that don’t parse, testing files, etc.

Our results above include 444 errored checks that without this improvement would be blocking developers – a hit to developer experience greater than that of the detected Known Risks themselves.

Compass metadata for dynamic filtering

Our Known Risks check has the opportunity to inspect every PR that occurs in Atlassian workspaces, but not all repositories require the extra oversight or safety afforded by our checks. Our highest level of Reliability practices and criteria are reserved for our Tier 0 and 1 services that are business critical.

Integration with Atlassian’s Compass GraphQL API allows us to identify the services associated with the repository of the current PR being evaluated and assess the associated Tier for those services. For non-production services or services in our less critical tiers, Known Risks passes automatically.

In our results above, over 145,000 (or 41%) of pull requests are automatically excluded and passed due to this filtering. Based on our detection rate this would have been another 109 pull requests, or 1.2 per day, that would have been unnecessarily blocked by Known Risks and subject to overheads in approvals and support.

Flexible approvals with Jira validation

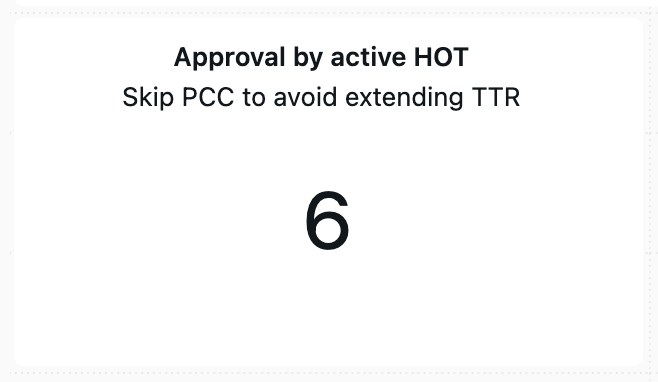

Blanket approval during incidents – During an active incident it may be that time pressure necessitates that we are prepared to hotfix something as quickly as possible. At Atlassian, incidents have a corresponding HOT ticket tracked in Jira: our Known Risks checks integrate with this Jira project to validate ticket status and allow for an active HOT to be used as approval for detected Known Risks.

In our 90-day results above we see HOT approvals used in approximately 3% of Known Risks cases, ensuring our Known Risks checks aren’t implicated in extended TTR.

Approval via Production Change Control (PCC) – The PCC approval tickets raised by service owners are validated on submission by Known Risks, verifying peer review and approval by asserting the correct status in Jira.

Approval via Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) – Standard operating procedures at Atlassian are tracked in an SOP Jira project, the issue key can be submitted to Known Risks as approval for common and pre-verified changes tasks to avoid overheads associated with planning production changes.

Extensions to Known Risks

Known Risks has provided a standard, platform-supported way to analyse configuration changes in Atlassian pull requests for issues and engage with a suite of integrations for approvals, exclusions, and data reporting.

Currently our set of Known Risks are curated and maintained by our central Reliability team, focused on general risks that might appear in any repository at Atlassian, such as our known service descriptor risks. But there is appetite from reliability-conscious teams that want the flexibility to be able to configure and detect their own additional risks that they are aware of in their own specific repositories and configuration – but leveraging and reusing the general framework on Known Risks.

Our future plans look to implement and provide an extensible Known Risks framework – where service owners can define and manage their own additional checks via .known-risks.yaml configuration file:

# schema to be defined - the future is bright for Known Risks

excludePatterns:

- **/test-fixtures/*

additionalChecks:

- includePatterns: [**/my-special-config/*.yaml]

sensitivePaths:

- *.foobarIndices.*

description: >

You are updating the FooBar indices - be aware that changes to these

indices cannot be rolled back without following the relevant SOP.

Please use the SOP and acknowledge: go/foobar-index-updatesAs Known Risks is already run against all pull requests, we can retrieve this file and apply any defined checks on behalf of the service owner!