Design thinking is the low-pressure way to figure out your career (and life)

Do you know when you hit a tipping point? There’s before and after that moment, and you can feel a change in your body in “the after.”

The one I’m talking about was a meeting with my boss in one of those conference rooms with clear walls, like a fishbowl, when she told me I didn’t get promoted.

I’d had a fun, intense, wild ride working at a late-stage startup. But three years later, I felt like a shell of a person. I was commuting ninety minutes each way to work. I was feeling uninspired, dreading the relentless marketing campaign cycles that at one time were exciting. I spent almost every meal in front of a screen and a lot of silent time with strangers on a commuter train. And when I’d finally come home I didn’t even like my neighborhood – it was too loud, too busy, not enough trees.

And why didn’t I get promoted? My boss told me I deferred too much to other people’s opinions rather than leading with my own. I wasn’t sure I wanted a promotion, but it felt like the natural exchange that happens when you pour all of your energy into your job and you’re told to keep up the good work. So, I decided to quit. I traveled solo for several months. When I got back to San Francisco, I moved farther from downtown and started thinking about what to do.

That’s when a friend handed me Bill Burnett and Dave Evans’ book Designing Your Life, and I discovered design thinking.

What is design thinking?

According to the Interaction Design Foundation, design thinking is “is a non-linear, iterative process that teams use to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions to prototype and test.” It’s a framework that organizations around the world use to get around natural human biases. It emphasizes defining challenges, ideating, noticing patterns, and just trying things out.

Design thinking has been so successful that several practitioners have started applying it to life and career planning, including authors Burnett and Evans, as well as Ale Wiecek, Founder and Chief Empathy Officer of Australian consulting firm SQR ONE. Wiecek gave a talk at the Atlassian 2020 Remote Summit titled “How to build a meaningful career (and life) with design thinking” where she outlined the principles of the methodology, and gave examples of applying these tenants to her own life.

Wiecek explains that reframing how you think is paramount to design thinking so that when there’s an inevitable roadblock or failure as you start a new job or launch a business or try a new project, you can learn from it and pivot.

For us non-designers, focusing on the problem instead of jumping to the solution may not come naturally. For example, how many of us, when faced with joblessness, might jump to start applying for the first open positions on the Internet we think we can get? But, if we want to create meaningful careers and life experiences, Wiecek says, we all have to embrace ambiguity and our curiosity. Here are some more examples from her talk of ways of reframing your thinking to be more like a designer:

| Design thinking is… | As opposed to… |

|---|---|

| Problem-focused | Solution-focused |

| Empathizing before forming conclusions | Jumping to conclusions |

| Comfortable with ambiguity and vulnerability | Discomfort with ambiguity and vulnerability |

| Open to failure | Afraid of failure |

| Iterative and agile | Waterfall |

| Optimistic | Less optimistic |

| Creative problem solving | Doing things the same way as before |

| Dependent on collaboration | Optional collaboration |

| Analytical and imaginative thinking | Critical and analytical thinking |

| Growth mindset | Fixed mindset |

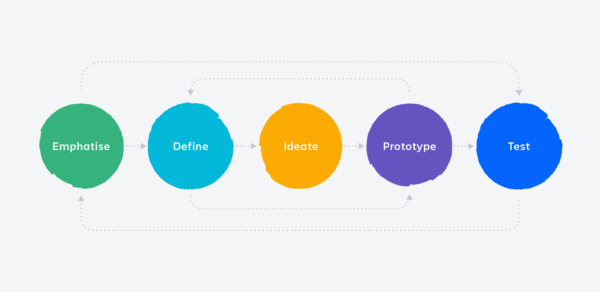

The five phases of design thinking

Although different design thinkers have variations to the methodology, Wiecek lays out the five underlying phases: Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test.

1. Empathize

The empathize phase is about recognizing and taking stock in your current situation without judgment.

When designing a product, this might mean empathizing with your customer or target customer. When using design thinking for your career and life, you have to, well, empathize with yourself.

When using design thinking for your career and life, you have to empathize with yourself.

When I got back from San Francisco, I posted up at a coffee shop to read Designing Your Life. I was surprised I got choked up right away in Chapter 1. Burnett and Evans talk about how at the design school at Stanford, there’s a sign outside that says “You Are Here.” The sign is a reminder to its students that “design thinking can help you build your way forward from wherever you are.”

I had recently thought of myself as “behind” in life. I felt disappointed that I hadn’t checked the boxes of traditional adulthood: I wasn’t in partnership, didn’t have children, I wasn’t blazing my way up a career ladder, and I hadn’t found my community. But, designers aren’t worried about what you haven’t done.

To move forward, what’s important is to recognize and write down what’s going well and what isn’t. According to Burnett and Evans, rating how you’re doing in the areas of health, play, work, and love help you calibrate. Six months after leaving my job, I rated “health” and “play” pretty highly. I had started a yoga teacher training program and was cooking a lot. I was taking advantage of life without a commute. “Work” and “love” were lower – I wasn’t working and was feeling wary of job postings but needed to start earning money again. I was living alone and feeling disconnected from family and close friends. It felt good to take a clear inventory.

2. Define

The define phase is where you take any data you collect to recognize patterns and trends and start to reframe your “problem.”

That could mean getting a clear understanding of your values through exercises like this one from Carnegie Melon or journaling about experiences and rating how energized or engaged you are by them. Burnett and Evans call this writing exercise the “Good Times Journal.”

By this point in my journey, an opportunity came up from a former colleague to work as a contractor on a project at Atlassian. So, when I started, I decided to rate my activities. I realized I felt engaged and energized after talking with customers or contributing my ideas to a brainstorm. I was less engaged by really technical discussions or when I was executing on an idea without understanding the “why” behind it. In my personal life, I got lots of energy from meaningful conversations with friends and studying yoga. I realized tracking my patterns takes curiosity and lots of patience.

3. Ideate

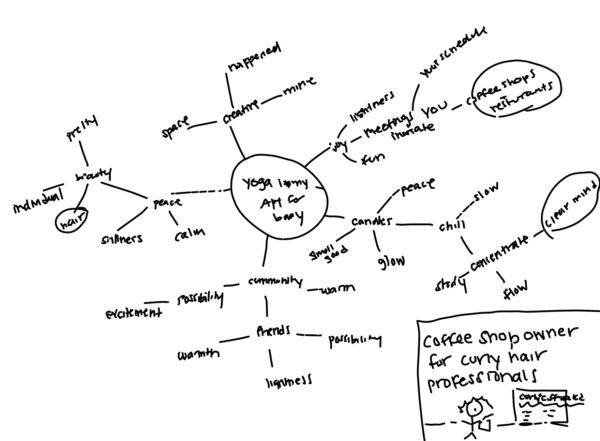

In the ideate phase, we take those trends and patterns and come up with lots of ideas for ourselves – some of them wildly impractical, others grounded in what’s in front of us right now. Wiecek stresses the importance of quantity over quality of ideas when brainstorming (which is another point: this is a great stage to do with others to get as many ideas as possible). Mindmapping is one way of generating ideas.

Burnett and Evans suggest taking moments that give you energy, where you’re engaged or in flow, and then putting those at the center of a piece of paper and then creating branches based on words that come to mind. And then creating new branches based on those words. Without thinking too hard about it, you then circle the words that stand out. In their version, you create a new job description (including a picture) based on the words you’ve circled.

While this exercise might seem silly, if you do it enough times, you start to see themes and patterns emerge. For instance, even though I didn’t circle them, the concepts of “community”, “possibility”, and “creative” came up in many of my mind maps.

4. Prototype and test

Prototyping is just what it sounds like: building a quick and dirty preliminary version of a job or life change and testing it out in real life.

What these mind maps and prototypes do is create so many ideas that they prevent us solution-jumpers (who are uncomfortable with ambiguity) from acting on our first idea without gathering data from our prototypes. So, rather than “making a leap of faith” as Wiecek puts it, start by prototyping in your current role or community.

For me, leaping to a big decision before prototyping might look like – after feeling uninspired by job postings and not getting a promotion – pivoting my career away from brand marketing to becoming a full-time yoga teacher or moving to a commune to solve my challenges with living alone, without trying out those experiences first-hand.

From my mind-mapping exercise, I realized that creativity came up a lot. While as a brand manager, I love rallying my team around creative work, but I also craved my own creative process. So I had what Burnett and Evans call “prototyping conversations” with two of my colleagues on the Atlassian editorial team to understand what it was actually like to write and strategize about content on a daily basis. I also taught a yoga class over Zoom, prototyping a teaching career, as I waded through the ambiguity and my fears of failure. Note: I will have many prototypes in my career and life planning before making a big decision.

Try it

Prototyping conversation: Sit down with someone who is in an expert in what you are interested in doing, ask them questions, and learn from their experience.

5. Activation

Eventually, we conduct enough tests that we’re ready to make a decision and activate on a career or life choice. Wiecek explains that to stay resilient and to make the right choices for us we must adopt a designer’s mindset and move through the fear of failure that ultimately comes up. “Fear will be our co-pilot” she explains. “If you fail, it’s OK. Changing careers is not failure. Trying something out that doesn’t work isn’t failure. Failure will be part of your life.”

Fear will be our co-pilot… Changing careers is not failure. Trying something out that doesn’t work isn’t failure. Failure will be part of your life.

Ale Wiecek

Whenever I hear that failure is necessary, it makes my eyes roll. I’ve been part of organizations that word-for-word demand perfection while at the same time asking us to take on big risks. But, as a designer learning to reframe, I’m learning that there’s no way to grow and make good decisions without testing.

I’ll admit I’ve not made any big decisions since starting this process. While living through a global pandemic, life design has definitely taken on a slower, more cautious pace. I’m grateful and fortunate to be healthy and working. Like many millennials, after working from home alone for several months I packed up to stay with my parents on the east coast for the summer. So, in a way, I’m still testing new experiences and staying curious, even under circumstances that are completely out of my control.

Wiecek also explains that by no means is this process linear. When we run out of ideas, it’s time to look back at our “define” and “ideate” phases. And our prototypes could lead us to dead ends. But, what’s energizing is growing and gaining self-knowledge by approaching career and life decisions with this new mindset.

The lesson from Wiecek’s talk that stuck with me the most is “No one organization will care about you the way you do… you must own and have that duty and care for what’s ahead, what’s important, what needs to be prioritized.” I could not agree more.