“Impossible alone, possible together”: Van Jones on the universal truths of teamwork

“If you want to do something monumental, you’re gonna have to work with people who look very different than you. Think differently. Pray differently. Love differently. Or you have no shot.”

Van Jones is perhaps most widely recognized as a political commentator on CNN. He’s also a thrice-published author; nonprofit cofounder many times over; former Special Advisor to President Barack Obama; and activist, advocate, and organizer on behalf of a wide range of causes and constituencies – environmental issues and prison reform in particular.

Kinda makes you wonder what he eats for breakfast.

At Atlassian Team ’23, I had the chance to chat with Jones about his background in cause work and grassroots organizing. I asked him about his perspective on how teams navigate strengths and weaknesses and stay focused on the task at hand – without a corporate mandate or the institutional resources we sometimes take for granted.

The people who work at Atlassian, and lots of folks in our orbit, converse in a common language around the skills, theories, practices, and frameworks that help groups of people achieve more than the sum of their parts – we treat teamwork as a discipline to be mastered. But most groups of people who are trying to achieve a common goal aren’t immersed in that school of thought, and don’t necessarily speak that language – they’re left to their own devices and instincts to achieve their goals.

With a wide-ranging breadth of experience and lessons learned, Jones is a gold mine of wisdom on getting sh*t done, sometimes under seemingly impossible circumstances. Here’s what he had to say about the universal principles of successful teamwork.

Stay human, always

Jones doesn’t mince words on this: “The most important slogan that I have is ‘stay human with each other.’ Any rituals – check-ins and check-outs, meetings, birthday acknowledgments – whatever it is, whatever keeps people remembering that the person in that little square in the Zoom conference is a human being with a whole life behind her. Everybody needs a little bit of grace.”

According to conventional wisdom and our own research, psychological safety – in a sense, the act of embracing humanity itself, with all its wins and losses – is a key element of high-performing teams. When people feel safe to engage in those acts of vulnerability – take the risk, share the idea, try the thing – more innovation and better teamwork happens.

To lay the groundwork for that culture of connection and vulnerability, at the beginning of a campaign, Jones shares, “We would often ask people, ‘What are you hoping for and what are you afraid of?’ That gives you so much to work with.”

When leaders or organizers frontload those fundamental truths, they unlock more active participation, change-making dialogue, and a highly motivating culture of recognition.

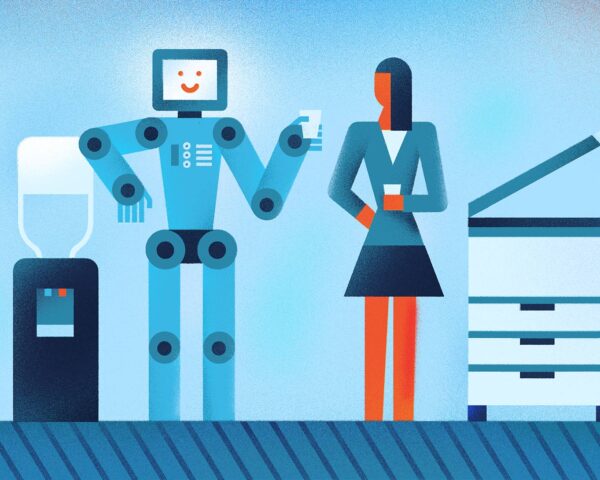

“Stay human” applies in the literal sense, too. We share Jones’ perspective that technology is supplemental to the human project, not a harbinger of its demise – partly because those most human elements of who we are will never become redundant. “When I was coming up, we didn’t have Slack,” Jones says. “And, you know, those technologies are really key. But as I’ve gone on in life, now that I’m dealing with better-resourced organizations, I find that those human touches still matter a lot.”

Remember that people want to be part of something special

Much like people tend to band together to “do life” – make a home, raise children, set the record for biggest flash mob – they need each other to achieve history-making, humanity-progressing goals. Of course, almost any collection of people can achieve more than an individual; more hands and minds tend to multiply the output of a group. But when teamwork is in motion, something extraordinary happens – something equaling more than the sum of a team’s parts.

“People want to feel like they are special people working in a special organization,” Jones says. “If they feel like the organization is special but they’re not, it doesn’t work. Or that they’re special and the organization is not, it doesn’t work.”

You’ve got to line up that unique spark of genius and magic. And the significance in that person’s journey. How does that line up with the journey of the organization? When you can line those two things up, great things happen.

People are drawn to extraordinary experiences. On one scale or another, everyone wants to make their own little sliver of history, whether their ultimate goal is to become a world leader, a renowned activist, an excellent parent, or the best software engineer they can be. In a very real way, then, part of a leader’s role is to sync up the thing that makes an individual special with those elements that make the organization or initiative special. As Jones puts it, “You’ve got to line up that unique spark of genius and magic. And the significance in that person’s journey. How does that line up with the journey of the organization? When you can line those two things up, great things happen.”

Maybe this manifests as hiring employees who genuinely embrace your company values, or customizing a volunteer opportunity to play to an individual’s particular strengths. Finding that sweet spot where a team and a team member harmonize – that’s what sparks the magic of collaboration.

Leave your ego at the door

Jones told me that “it takes leadership to go from a small circle of self-righteous, homogenous people to a big network of people” who are actively achieving things. Generally speaking, a goal-oriented group needs a leader to act as a guiding light and a common thread to unite disparate personalities and keep all eyes on the prize. But leaders and followers alike – especially those who are making sacrifices in the name of a cause – are human and fallible, and sometimes our egos stunt our progress.

“The shadowy side of people who are working on causes is that we sometimes have a sense of moral superiority,” Jones says. “We sometimes fall into the trap of: we’ve given up so much to be a part of this – because if you work in the not-for-profit sector, you’re making pennies to the dollar of what you can make in the private sector – and you can get wrapped in a cloak of self-righteousness that blinds you to your own limitations, your own foibles and flaws. We always run the danger on the cause side of actually becoming what we’re fighting.”

In every industry, and at all points on the pay scale, hubris lurks and self-awareness is universally beneficial. Effective communication, constructive feedback, and empathetic conflict resolution practices are clutch for small circles and large groups alike.

Stay focused on the people who need you

On this point, my lived experience as a corporate blog editor and Jones’ as a grassroots organizer are radically different. I find joy in storytelling and in helping people work better together, and I do that at a for-profit company. I’m proud to work for an organization that prioritizes customers and corporate citizenship, but the stakeholders I’m beholden to – and the ways in which I’m beholden to them – have needs on a different scale than the populations served by, say, the First Step Act, the 2018 bipartisan prison reform bill Jones championed.

But empathy and care aren’t zero-sum resources, and there’s a lot we can learn about professional integrity from someone who’s been in the thick of literal life-or-death cause work. Being there for each other, and showing up for the people we’re obligated to – whether that’s an incarcerated individual, a member of our community, a teammate, or a customer – that’s the signal. And the hubris, infighting, grandstanding, and short-sightedness – that’s all just noise, from our stakeholders’ perspective.

“The people who need us don’t care about all this crap,” Jones says. “They don’t care about who voted what way, or who said what on Twitter, or who’s got the better philosophical position. They just need help. And they’ll take help where they can get it.”

Harness the power of hindsight

Hindsight is, yes, 20/20, and it’s free, and there’s perhaps no better tool for teasing out what’s working and what isn’t. Jones names this practice as fundamental to the success of the countless campaigns and movements he’s been a part of. “At our best,” he says, “we would evaluate everything…what could have gone better in the preparation, what went well in preparation? What could have gone better and what went well in execution?”

Jones also ties that very human act of embracing successes and failures alike to the “hopes and fears” conversation he uses to kick off a project: “If on the front end, you ask people about their hopes and their fears, and on the back end you let people evaluate, and you do it in a group so that everybody can hear everybody – from the intern to the president – it’s amazing how quickly a team can get strong.”

Whether you’re putting a man on the moon or coordinating boots on the ground, whether you’re fluent in the corporate language of teamwork or you rely on the scrappy genius of cause work, a team of individuals can achieve more than the sum of its members. Leaning on our common humanity, setting aside our personal grievances in favor of what matters most, and maintaining our focus on what makes us collectively strong – that’s how Big Things get done.

In Jones’ own wise words: “Impossible alone, possible together. That’s got to be the cornerstone of doing anything consequential, monumental, significant. You can do itty bitty shitty stuff with your high school buddy, or with people who just vote like you or pray like you or look like you. You can keep yourself busy. But If you want to do something monumental, you’re gonna have to work with people who look very different than you. Think differently. Pray differently. Love differently. Or you have no shot.”