Being a well-rounded person doesn’t pay anymore — here’s what does

As a jack of all trades, you’ll never set yourself apart from anyone else. It’s time for a new approach to professional development.

Oh, to be a well-rounded person. The person who can speak a second language while running a marathon, then knock out a shift as a volunteer paramedic – all before sitting down to family dinner. Well-rounded people are considered interesting. Sophisticated, even. Well-roundedness is one of the most sacrosanct ideals in Western society.

But is it still useful?

We now live – and more importantly, work – in an era of specialization. For GenX’ers and older Millenials, this is a brave new world compared to the one we watched our parents work in. Remember those dinner table conversations in which they insisted we complement our math and science requirements with a few arts and humanities electives? That was solid advice… at the time.

Over the last 20 years or so, trends in technology, manufacturing, and public health have increased the need for skill sets that emphasize depth over breadth. (GenZ, take note.) To be sure, going broad is great when it comes to personal interests, and might benefit your professional endeavors as well. But choosing an area to go deep on is crucial for your career development and long-term success whether you’re pre-career, early-career, or mid-career.

Understanding our obsession with well-roundedness

The concept of being well-rounded dates back to ancient Rome and Greece, where knowledge of art, logic, and philosophy was considered essential for free citizens’ ability to engage in public life. In Medieval times, music, astrology, and geometry were added to the canon of well-roundedness, though by that time such education had become the exclusive domain of the elite.

By the late Renaissance and Baroque period, European universities had taken up the torch of liberal arts. It then spread to the Colonies where wealthy men received liberal arts educations modeled after Oxford and Cambridge. Although these same men took up powerful positions in finance, industry, government, and the military, they expected to learn the specifics needed for their posts on the job.

In other words, well-roundedness has historically been associated with status whereas focusing on a skill smacks of having to do *gasp!* manual labor for a living. Plus, the appeal of being a jack of all trades is undeniable – until you remember the part about being a “master of none”.

More recently, getting a degree in the humanities or social sciences was considered a good choice because of how “flexible” it is and how it can “take you just about anywhere”. Trouble is, it’s increasingly leading graduates into financial woes as they struggle to pay off student loans. According to data aggregated by Bankrate, the salaries of most humanities and arts majors barely reached $40,000 in 2017 and their unemployment rate hovered around 4.5%. Compare that to skill-focused majors like pharmaceutical sciences and electrical engineering, where unemployment is closer to 2% and six-figure salaries are the norm.

The case for investing in your strengths

If you’re starting to regret your comparative literature degree, take heart: all is not lost! You probably don’t need an educational do-over. Chances are, you’ve discovered a handful of strengths during your career thus far. The secret to professional development in the 21st century is to double-down on them.

It may sound counterintuitive, but your strengths actually provide your biggest opportunity for growth. If you’re naturally good at something to start with and you enjoy it, your potential is virtually unlimited. You’ll also experience a virtuous cycle of growth leading to higher confidence, which promotes better performance and inspires you to keep growing.

Viewed another way, there’s no sense spending all your energy on your weaknesses, then having no gas left in the tank for developing your strengths. To paraphrase one group of researchers, why should a natural pitcher struggle to become a mediocre right fielder?

Before you permanently hunker down inside your comfort zone, however, understand that even electrical engineers and pharmacists do better when they challenge themselves to acquire knowledge from other fields.

The rise of the T-shaped professional

Growing your strengths is a key component of becoming a “T-shaped” professional – a concept popularized by Tim Browne, CEO of the design firm IDEO. The “T” symbolizes being competent across a wide range of skills, but going deep on one and making it your specialty. For example, I’m competent in SEO, web publishing, social media marketing, and copyediting, but writing is where I shine. Or take credit card fraud protection, which involves coding, law, finance, and psychology. You need a team whose members each specialize in one discipline, but have considerable knowledge of the others.

Being a jack-of-all-trades sounds great… except that you’re a master of none.

T-shaped individuals are highly sought-after. (For proof, look through job postings in your field and see how many “generalist” roles you find.) Although schools are starting to emphasize this model, T-shaped professionals are particularly hard to find amongst younger workers fresh out of college. The sooner you fit yourself to this mold, the sooner you’ll stand out from the crowd.

Don’t take this as a license to ignore your weaknesses entirely, however. If you neglect them year after year, they may become a liability. Besides: if you always walk away from things you’re not immediately good at or don’t like, your self-discipline muscle atrophies in a hurry.

How to identify your strengths vs. skills

Don’t mistake “things you are good at” for your strengths. Most of us have some overlap in our sets of strengths and skills, so here’s how to tell one from the other.

Strengths:

- things you have a natural talent for or predisposition toward

- promote focus and give you an energy boost when you use them

Skills:

- capabilities you’ve developed

- might be things you actually enjoy doing

In a perfect world, you’d only need skills that match your strengths. In reality, becoming a T-shaped professional means adding a few skills that feel neither natural nor enjoyable. As you think about where to go deep, however, let your strengths be your guide.

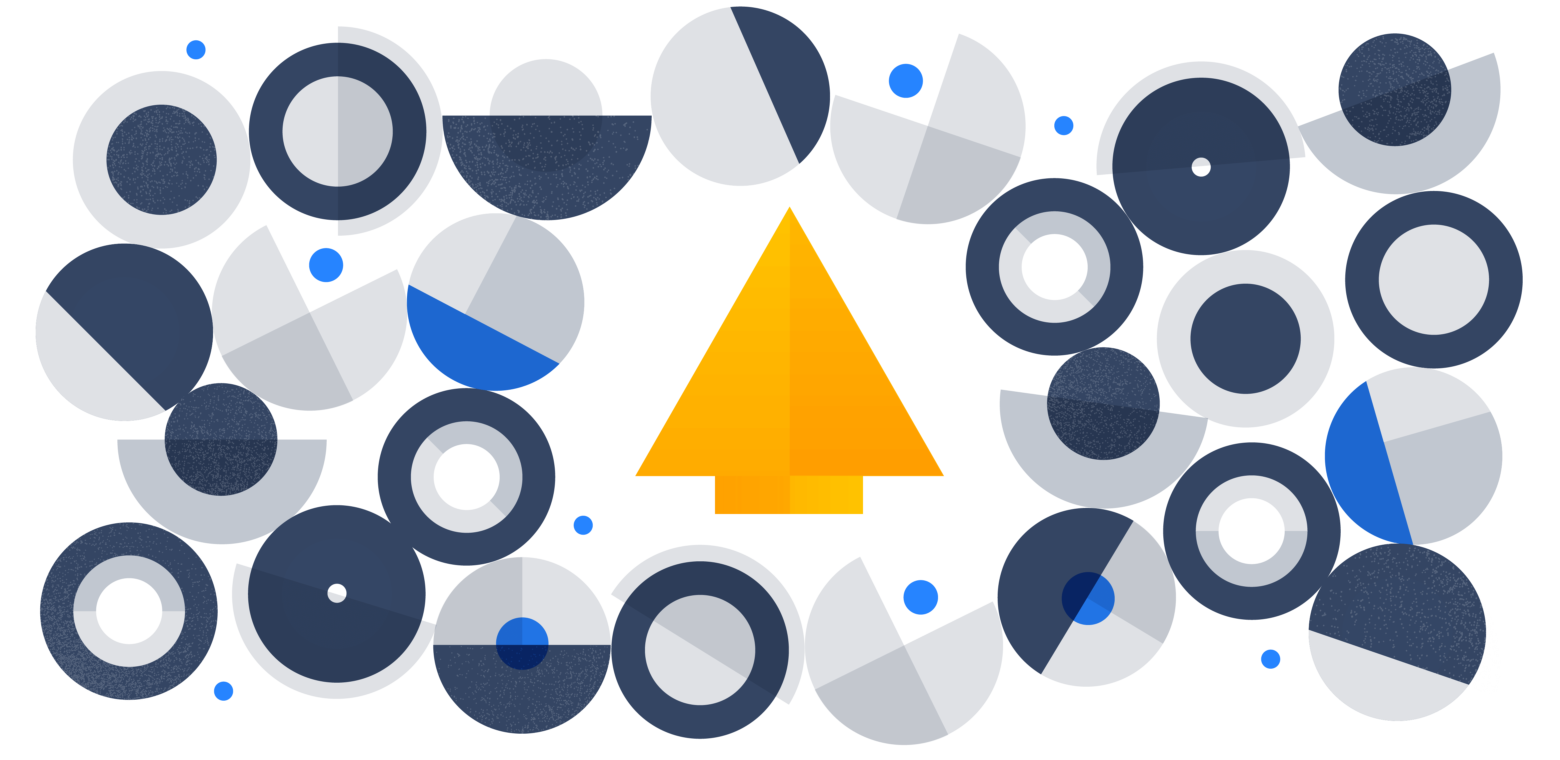

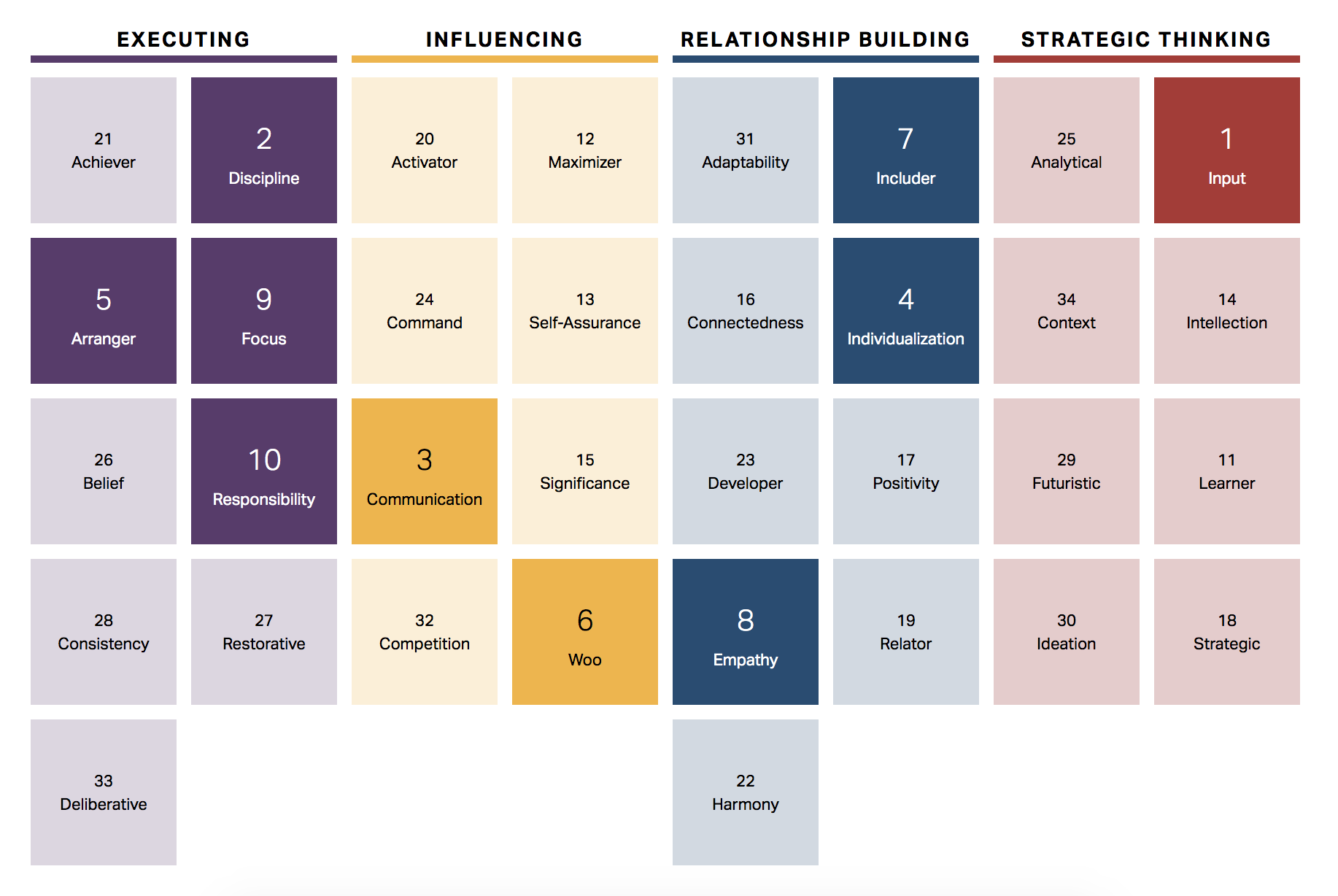

If you’re looking for a structured and researched-backed way to identify your strengths, there are assessment tools available, such as the popular CliftonStrengths ($50). Tools like these compile a portrait of you by asking questions about your preferences and habits. The trick is being brutally self-aware and yet self-accepting as you choose your answers. Here’s how mine came out (34 possible strengths were assessed across four categories, and my top 10 are highlighted in the bolder colors).

For an assessment that is untainted by your own biases and blindspots, try the Reflected Best Self (RBS) technique, which you can use at no cost. In a nutshell, you’ll ask family, friends, and colleagues to describe what they see as your best qualities and illustrate with examples. You’ll then look for patterns in the feedback to identify your strengths so you can make smarter career moves and perform better at work. Full, step-by-step instructions are here.

Used in combination, these two styles of assessment paint a rich, holistic picture of your strengths.

Note that strengths may or may not speak directly to job roles or specific fields. For example, I’m strong on communication and focus, both of which help me succeed as a writer. But these strengths could just as easily point someone toward working as a financial planner. Within the context of your career, use assessments like these to get directional information as to what to dive deeper into (the downstroke in your “T”) versus what to acknowledge and accept as a weakness.

Keep in mind that your strengths may evolve over time. And your professional environment will certainly change. You might be perfect for a job role that doesn’t even exist yet! Reassess them any time you’re considering a major career shift like getting into management, getting out of management, changing industries, or moving into an entirely new field. Even if you’re staying the course, it’s worth re-assessing every 3-5 years.

Whatever your strengths are, play to them.